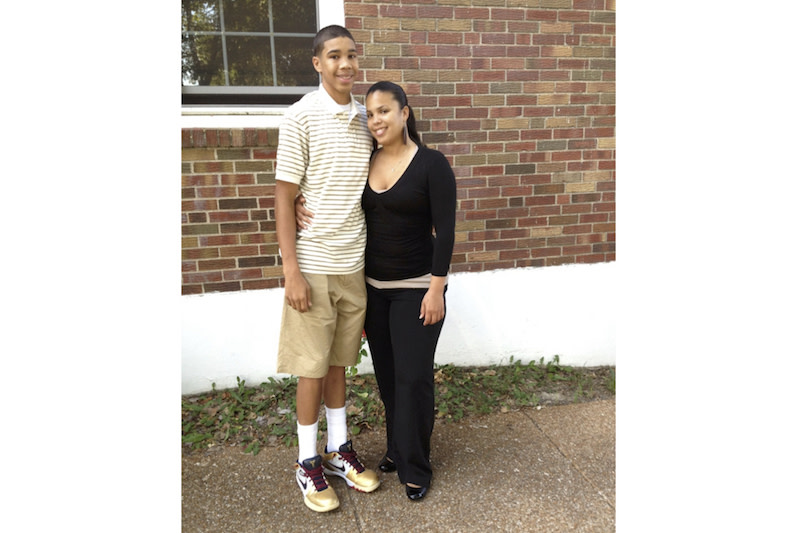

Sure, there are many difficult periods to pick from. When bills go unmet for months on end. When the power was turned off. For a few years, Jayson Tatum shared a bed with his mother, Brandy Cole. They didn’t have any furniture for a while.

But that was simply the kind of problems and struggles you’d expect as the sole child of a single mother who had you at the age of 19. And Cole kept her son somewhat out of it. She was adamant that, regardless of the statistics regarding teenage parents, she would succeed and he would learn from her. So she didn’t let him be concerned about his daily challenges at those times.

Her goal was always to show him that they were on the right track.

But one day, when Tatum was in fifth grade, he couldn’t hide from reality any longer.

Cole had left her mother’s house when Tatum was six months old, wanting a life for the two of them. She acquired a little two-bedroom, 900-square-foot property in University City, St. Louis. There was a small backyard, a chain-link fence, and, most significantly, a roof over their heads.

The house had one more feature that day.

Cole drove her kid home from school, when Tatum noticed a pink piece of paper posted to the front door. A foreclosure notice.

“And she started crying,” Tatum recalls. “I had no idea what to do.” I simply felt helpless. I was desperate to assist. But I was just 11 at the time.”

Tatum’s mother went inside, feeling betrayed by her son. The mother and her son swam in their grief for an hour or two.

That was the lowest point. Tatum, now a top NBA draft prospect following a great freshman season at Duke, recalls it vividly. But not merely because of the sensation of having reached rock bottom. Because of what transpired after that.

Cole blinked her eyes closed and gazed at her kid.

“All right,” she said. “I’ll work something out.” I always have.”

Tatum was in first grade when he was asked what he wanted to be when he grew up.

The answer was simple. Of course, he’s an NBA player. The teacher laughed. Choose a profession that is reasonable, she advised Tatum. Change your expectations.

“I was furious,” Cole adds. “The next day, I went to school and talked to the teacher, and it wasn’t like a two-way conversation.” ‘Ma’am, with all due respect, I don’t believe it’s acceptable to tell him that’s something he can’t achieve when I’m at home teaching him anything he can dream is attainable,’ I remarked.

But their two-bedroom apartment was all about doing, not dreaming.

Tatum’s mother was only a few months away from starting college when she discovered she was pregnant. Why did you leave? No. The single mother gave birth during spring break and returned to class the following week. Then she simply brought her toddler to class. He continued to accompany his mother to classes: undergrad, law school, and business school. With her son sprawled over the foot of her bed, she’d be studying for law school. He’d leaf through her real estate law books. “I don’t want to read these kinds of books, Mom,” he’d remark. “I want to play basketball.” “Well, you’d better work really hard,” she’d say.

He did exactly that. Every morning at 5:30 a.m., he’d enter his mother’s room and say, “I’m gone, Mom. “I adore you.” Then it was on to the gym for a 90-minute workout before class.

He just kept working and working and working. — Jayson Tatum’s high school coach, Frank Bennett

“I get to school around 6:30 a.m. every day, and he was here at 5:45, 6 a.m. at the latest, getting his work done,” says Frank Bennett, Tatum’s coach at Chaminade Prep in St. Louis. “What’s impressive is that he did it every…single…day!” I recall the one and only time he left. It was the day after we had won the state championship. That was his one and only day off.

“It’s just him. He just kept working and working and working.”

Tatum’s father recalls the moment he discovered his kid possessed a unique skill. Tatum was in fifth grade, playing in a league with adult guys, and averaging 25 points per game. “The older guys were like, ‘Hold on, how old’s this kid?'” Justin Tatum chuckles.